The onslaught of misguidance: philosophy and science

Prof. Carlo Fonseka

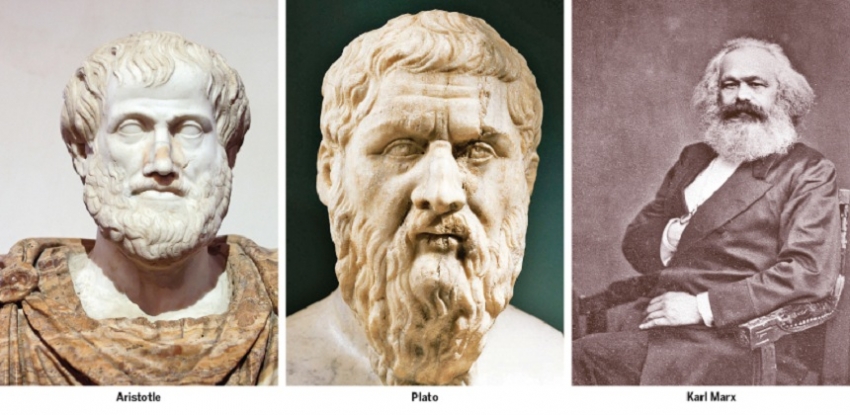

The aim of this essay is to explore the question of whether the central doctrines of Buddhism can be understood as constituting part of empirical human knowledge. In contrast to rationalists, empiricists claim that everything human beings have valid knowledge of has been acquired through the senses, that is to say, from sensory experience. The classic formulation of empiricism came from Aristotle (384-322 BC).

Declaring that profitable inquiry has to confine itself solely to the world of actual or possible experience, he said: “There is nothing in the mind except what was first in the senses.” Aristotle's assertion was made to counter his teacher Plato (c.427-347 BC) who taught that human beings are born with knowledge of idea such as justice, beauty and courage independently of and prior to their experience of the real empirical world in which they live, that is to say, with a set of ‘innate’ cognitive ideas.

In the 17th century, the British empiricist John Locke (1632-1704) repeated Aristotle's words to counter the rationalist Rene Descartes (1596-1650), who declared that reason is the only path to knowledge. In contrast to empiricists, rationalists contend that the exercise of pure reason is capable of generating knowledge independent of sense perception.

Empirical method

Self-evidently, the knowledge on which the whole apparatus of modern civilization, consisting of computers, the internet, television, radio, telephone, the printing press, motor vehicles, ships, airplanes, microwave ovens, fertilizer, antibiotics, kidney machines, cardiac pace-makers, weapons of mass destruction – the list is endless – is built has been acquired by the empirical methods or scientific method that essentially involves observing events pertaining to a given natural phenomenon, hypothesising about possible causal relationships between the relevant observations, and experimenting to test the validity of the hypotheses. In summary, the empirical method involves observation, hypothesis and experiment.

Thus, both the first step and the final step in the empirical or scientific method involve observation, i.e., sense perception. Sense perception is, therefore, the beginning and the end of the empirical approach to knowledge. Empiricists contend that sense perception, if not indeed the sole legitimate source of knowledge, is certainly the final court of appeal concerning the validity of any given belief about the external world. And given the power to change the world that scientific knowledge has conferred on humankind, empiricism has emerged as the reigning theory of knowledge.

It is in this context that the question arises of whether the central doctrines of Buddhism too form a part of empirical human knowledge. Implicitly, to people who swear by science, the credibility of Buddhism will increase in proportion to the extent that its central doctrines are empirically authenticated. But it must be borne in mind that for all its cognitive power, empiricism as a theory of knowledge does not and in truth cannot guarantee absolute certainty. This is because empiricism depends on inductive reasoning and mathematics (the language in which, as Galileo said, the book of nature is written), which says that the probability of a universal generalisation being absolutely certain is zero irrespective of the number of observations on which it is based.

The stock example used to illustrate the limitation of induction is the generalisation based on millions of observations that ‘all swans are white.’ Europeans had, for centuries, believed it almost as a ‘natural law’ that all swans are white. When they discovered the existence of black swans in Australia, however, they realised that even a generalisation based on millions of observations could be invalidated by the next empirical observation. Thus, no finite number of observations, however large, can logically entail a universal generalisation. When we successfully infer the future, we do so on the basis of tentative generalisations suggested by (necessarily incomplete) empirical data and not on the basis of principles which are logically necessary. It is with this limitation of empiricism in mind that we must explore the relationship, if any, between Buddhism and empiricism.

Preached by the Buddha (c. 563-483 BC), Buddhism is one of the great religions of the world. As Karl Marx perceptively judged, among other things, religion is the generalised theory of this world, whether they are religious, philosophical, scientific or just fanciful in origin, all seek to account for the incredible diversity and intricate complexity of the phenomenon of life on earth. Historically, the convention has privileged religious theories against critical evaluation, but increasingly and irreverently all theories about the world including the God-hypothesis have become subject to critical empirical scrutiny. As Richard Dawkins says in his book The God Delusion, “notwithstanding the polite abstinence of Huxley, Gould and many others, the God question is not in principle and forever outside the remit of science.”

Religion, philosophy and science are aspects of humankind's ceaseless attempt to solve existential problems. Their concerted, dedicated, objective is knowledge of the world we find ourselves in, not knowing whence we came nor why nor whither we shall go. The most useful knowledge would provide us with an understanding of the world as it really is. According to the Buddha, too, the senses should be cultivated to see the truth, to see things as they really are. Such knowledge is necessary for human beings to pursue with any hope of success the goals of survival of themselves and their kind in this world, avoidance of suffering and attainment of happiness.

The starting point of this inquiry is the universally observable fact that human beings struggle to survive in this world, suffering to a greater or lesser degree in the process, but seeking to attain happiness. In order to survive and to avoid suffering and to attain happiness, appropriate knowledge is a sine qua non because it provides the basis for understanding our condition in a constantly changing environment.

The brain is the organ that mediates our continuous internal adjustment to the continuously changing external world. The brain scans the environment continuously and computes the answer to a recurrent question: What is the best thing to do in the given circumstances to survive and thrive in this world? The brain is equipped to perceive what happens around us as matters of cause and effect, however imperfect or inadequate they might be. It is from such a condition of uncertainty based on ‘naïve realism’ that we struggle “to grasp this sorry scheme of things entire.” The problem of knowledge is how it comes about that human beings, equipped as they are with notoriously fallible senses, can ever acquire trustworthy knowledge about the world.

Traditionally, the study of the problem of knowledge has belonged to the province of philosophy. Some regard philosophy as something intermediate between religion and science. Like religion, it deals with matters such as the ten questions that were ‘left aside, unanswered and rejected’ by the Buddha. However, like science, philosophy attempts to answer such questions by recourse to intellectual analysis rather than to faith-based authority of one kind or another.

According to Bertrand Russell, “all definite knowledge.... belongs to science; all dogma as to what surpasses definite knowledge belongs to theology. But between theology and science there is a No Man's Land, exposed to attack by both sides; this No Man's Land is philosophy.” But there are philosophers like WV Quine who think of philosophy as being continuous with science, indeed, as being part of science. He says that “philosophy lies at the abstract and theoretical end of science.”

Buddhism's uniqueness as a religion

As a religion, Buddhism is unique because it does not share the typical characteristics of classical historical religions. Huston Smith has identified six features which almost all major religions share. They are authority, ritual, speculation, tradition, concept of divine saving grace and mystery that was based on intense self-effort. An intellectual approach to the human predicament which is devoid of authority, ritual, speculation, tradition, the concept of divine saving grace and mystery is virtually indistinguishable from philosophy. According to the Buddha, the principle of dependent arising – a central doctrine of Buddhism – is something to the Buddha, the principle of dependent arising – a central doctrine of Buddhism – is something that the “Tathagatha comes to know and realise and having known and realised, he describes it, sets it forth, makes it known, establishes it, discloses it, analyses it, clarifies it, saying: ‘Look'.” That is precisely what a modern empirical scientist does, too. Therefore, the question of whether, and if so to what extent, the central doctrines of Buddhism comprise part of empirical human knowledge is meaningful and answerable. In Buddhist terms, it belongs to the category of vibhajja vyakaraniya.

In the western world, the pervasive influence of empirical knowledge embodied in science on all aspects of human life brought it into conflict with religion. If traditional religion was to retain its hold on the imagination of educated minds it had to come to terms with empirical science. Of all great religions, Buddhism has been the least vulnerable to the intellectual onslaught of science. In these circumstances, some Buddhist scholars have dared to look and see how far Buddhism's central doctrines are in accordance with empirical science.

Emergence of pragmatism

Many of the spectacular triumphs of science came in the 19th and 20th centuries. Philosophers saw that it was in science that humankind had acquired the most trustworthy and useful knowledge. An inevitable question posed itself.

What is the basis of the phenomenal success of science? Three American philosophers who were born in the 19th century and died in the 20th addressed that question. They are collectively known as pragmatists. They were CS Peirce (1839-1914), William James (1843-1910) and John Dewey (1859-1952). Peirce was the pioneer pragmatist in western philosophy. His signal contribution was the formulation of a theory of meaning which has had wide applicability in science and philosophy. He was concerned with conditional statements, i.e., statements which assert that if such and such antecedent conditions prevail, then such and such observable results would ensure. The essential point in his theory of meaning is that meaning must always relate to something observable that happens as a result of something we do, hence, the term ‘pragmatism’ which derives from the Greek word for deed or action. The practical value of this approach is that if the invariant conditions are recognised then the future experience can be predicted in the light of past experience. In the context of the present paper, the virtual identity of the pragmatic theory of meaning and the Buddha's concept of dependent arising (paticca samuppada) commands attention.

When this is, that is,

This arising, that arises,

When this is not, that is not,

This ceasing, that ceases.

The pragmatism of William James often assumed the form of a theory of truth. For him, an idea is ‘true’ so long as to believe it is profitable to our lives, and if the hypothesis of God works satisfactorily it is true. Thus for James what ‘works’ is ‘true'. In fairness to pragmatism, it must be pointed out that Peirce had serious objections to James’ theory of truth. In the scientific approach to reality, human happiness does not provide the motivation to understand the true nature of the world. Because experience shows that some of our beliefs are of doubtful reliability, Peirce set out to devise a technique for dealing with doubt. Dewey refined and elaborated it.

The technique is the method of revising our beliefs by inquiry, because of no belief can we be absolutely certain. Thus, Peirce was challenging the traditional view that real knowledge is based on certainty. He coined the term ‘fallibilism’ to characterise the very foundations of science. For Peirce to say that a belief is true is to say that it is destined to be accepted if inquiry continues. He has been credited as the forerunner of Karl Popper.

To talk of Karl Popper is to think of the Vienna Circle of Logical Positivists and Ludwig Wittgenstein who, though they did not themselves belong to the Vienna Circle, nevertheless profoundly influenced it.

Ludwig Wittgenstein's Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (1921) became the gospel of the Logical Positivists. And positivism has been regarded as a philosophical defence of science and mathematics, which are regarded as the supreme ways of exercising human rationality and gaining knowledge. In later life, however, Wittgenstein judged that his Tractatus was fundamentally in error, but the definitive statement of his repudiation of it came only in his posthumous publication called Philosophical Investigations (1953).

From 1939 until 1947 Wittgenstein was a professor of philosophy at the University of Cambridge. During this period, he published almost nothing. His second philosophy was disseminated only to and through his students. As it happened, one of his students during that per