Long, long, before India was divided into the present day Afghanistan and Pakistan, there existed a great state called Gandhara. Nestled in the Peshawar basin in the northwest portion of the ancient Indian subcontinent, the centre of the region was surrounded by the Sulaiman Mountains on the west.

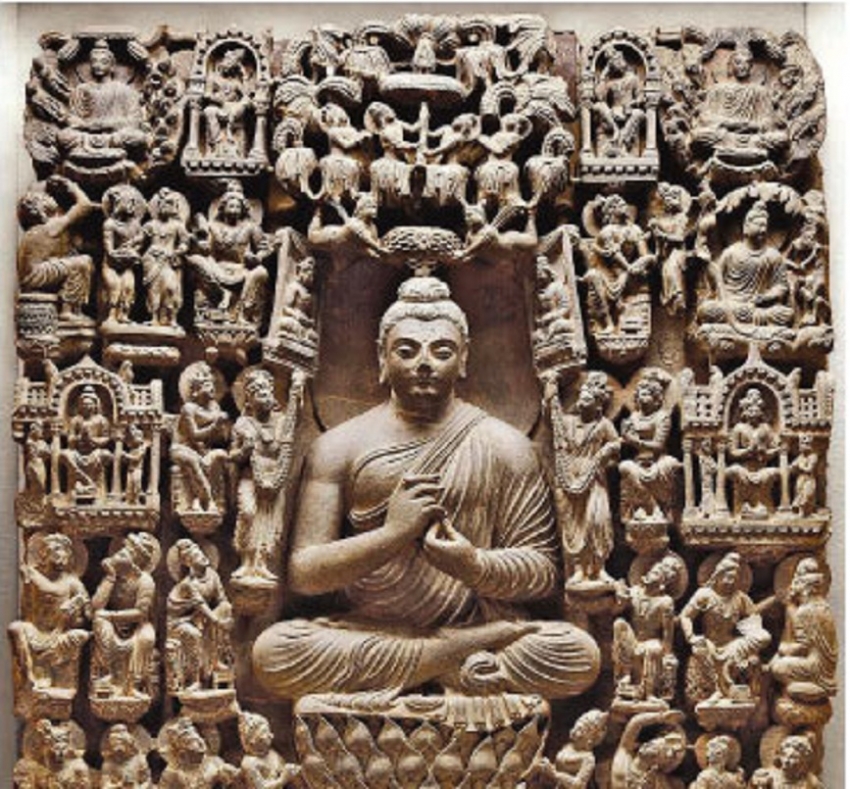

The Buddhist sculptural art of Gandhara has kindled the scholarly passion on many grounds. The region provided the symbiotic grounds for the propagation of the Buddha’s teachings and related art from India through the Silk Road to Central Asia, China and the distant east. With this being the case, the Gandhara culture was not established overnight. The sculpture silently assents the influence gained from miscellaneous states and its diverse imagery.

The seminar on ‘Buddhist and Gandhara Civilisation: The Cultural Nexus between Pakistan and Sri Lanka’ held at the Buddhist and Pali University, Homagama, was a cumulative effort to explore the variety of themes and influences. Pigeonholing the illustrious annals of Gandhara into the confines of a one-day seminar can be deemed an unjustifiable mistake. Yet, such a step, however small it may seem, will open up the paths to far-reaching interests on the millennium-old civilisation.

As Professor Hugh Van Skyhawk from Mainz University, Germany, based his comprehensive presentation on the Hellenistic influence, he enlightened the audience on how the combine of Graeco-Roman and Indian Buddhist culture is reflected in Gandhara art dating to the early centuries.

Both civilisations flourished on par with each other. King Alexander the Great enjoyed a short life span between 356 and 323 BC whereas his Indian counterpart lived between 321 and 297 BCE. But Chandragupta was more than a counterpart to Alexander. Following Alexander’s death, Chandragupta took the northern Indian subcontinent under his rule. This may be the preliminary grounds that paved the way to Hellenistic influence on Gandhara art. Chandragupta’s empire flourished for generations with one of his grandsons, Ashoka, making a noteworthy impact on the empire.

Kurt A Behrendt is more elaborate about the Macedonian king in his ‘The Art of Gandhara in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’:

“In 327 BC, the Macedonian King Alexander the Great conquered the regions of Bactria, Gandhara and Swat. After his death, these areas came under the control of his generals, and the Indo-Greek kingdoms thus formed were, at least initially, considered part of the larger Hellenistic world. Dating to the period is the Bactrian city of Ai Khanoum in Afghanistan, occupied from the fourth century BC to about 145 BC, which had many characteristics of a Greek colony. Indeed, the art made in Ai Khanoum near the time of its founding is Hellenistic in character; the product not of foreign contact, but rather of Greek artisans working for a local audience.”

The Greek influence

The Greek influence is evident to a significant extent on hair, robe drapery and footwear of the Gandhara statues. The statues at times resemble the Greek divine hero, Heracles. The shape of the Buddha’s robe draws a distinction. His standing posture is similar to that of a Roman king. These notable factors of the Gandhara Buddhist statues stand alone in significant contrast to the sculpture elsewhere.

Ayeshi Biyanwila brings up an attention-grabbing mention in ‘Origin of Gandhara Art; a Culmination of Greek and Indian Influences’.

“For Kim of Kipling, Gandhara art was consisted of the larger figures of the Greco –Buddhist sculptures done…by forgotten workmen whose hands were feeling …for the mysteriously transmitted Grecian touch. Gandhara art is neither Greek nor Buddhist.”

Influences can be attributed to the Hellenistic style. But iconography remained essential Indian. Balochistan University former Vice Chancellor Agha Ahmad Gul made reference to this aspect.

Gandhara sculpture is a melting pot of different religions and ethnicities. This phenomenon has animated the centuries ever since the Buddha’s teachings were established as a religious institution. The Balochistan academic was to point out the existence of other religions equal to Buddhism: Jainism, Greek gods, Zoroastrianism and the oldest, paganism. That explains the visitors from many areas.

The visitors include Achaemenids, Maurya, Indo-Greeks and Scytho-Parthians (who is not much referred to in history). As Gul elaborated, these visitors cannot be called crusaders or invaders. Visiting mostly sojourn purpose, these outsiders contributed to territorial expansion.

Iconography is the study or interpretation of the visual images and symbols used in a work of art. Symbolism existed as long as human civilisation prevailed, and was initially confined to anthropomorphic boundaries. The subject expanded its boundaries later into an anthropocentric region. As a result, symbolism came to be heavily present in Buddhist art in order to depict various forms and features related to the Buddha’s teachings and life.

First signs of evidence are found in the arts of Mathura the Greco-Buddhist art of Gandhara. Symbolic innovations of different platforms emerged down the line.

As Gul pointed out, the Gandhara iconography pays attention to the birth of Siddhartha, the death of Maya and the treasures (ten and seven). This engaging trend leads us to the Gandhara understanding of the Buddha’s life.

In chapter 25 of Buddhism, Islam & the Arts of West & Central Asia, David Juliao whose expertise is architecture, arts and design, digs into the main facets of Islamic and Buddhist art from those regions. Closer to the Tibetan plateau, Buddhist architecture developed in the form of stupas and monasteries. Painting and sculpture were also deeply influenced by Buddhism, and most of the artwork was of a religious nature.

Dr. Ghani-ur-Rehman, Director, Taxila Institute of Asian Civilisations, took this point forward. He elaborated how the Gandhara Buddhist sculpture gave rise to Muslim mosque art sometime later in ancient history. With graphic evidence, he substantiated how the two religions existed in reconciliation. The highlight of his examples was the wooden mosque swat (swastika).

Dr. Sardar Ali, Director General, Higher Education Commission, Pakistan, made an intriguing comparison between Sri Lanka’s Avukana Buddha statue and the Bamiyan Buddha statue. The statues, in his verdict, elucidated the Buddha’s teachings.

Another take-away point of the seminar is the individuation concept. Widely used in philosophy and allied subject areas, the concept elaborates the manner in which a thing is identified as distinguished from other things. Interestingly it is applicable to the Gandhara civilisation, as it stood unique. The style was unique especially owing to the compelling fusion of foreign styles that ultimately gave visual form to Buddhist religious ideals in northwest Pakistan and Afghanistan.

Kurt A Behrendt also makes reference to this fact: ‘More sculpture and architecture made in the service of Buddhism has been found in Greater Gandhara than in any other part of ancient South Asia. Behrendt, however, cites a few limitations: poor quality of early excavations, the paucity of ancient written records and inscriptions and the deliberate destruction of large portions of Afghanistan’s cultural heritage. The British military intervention led to scientific, proper and systematic excavations.

Buddhist art and culture

The seminar on ‘Buddhist and Gandhara Civilisation: The Cultural Nexus between Pakistan and Sri Lanka’ holds much weight on two grounds. First, it was held at the Buddhist and Pali University. Second, the seminar was organised in collaboration with the High Commission of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan.

Buddhist and Pali University offers archaeology as well as a subject to be specialised. Archaeology is now expanding its wings to strengthen synthesis for a better understanding of the global phenomenon.

Pakistan, on the other hand, has been the cradle of Buddhist art and culture and the second holy land of Buddhism for well over a thousand years. The religious faith has marked the most significant epoch in the history of the cultural and social evolution in the subcontinent. Indeed it has been one of the greatest spiritual experiences the world has ever seen and which have left behind one of the finest manifestations in the domain of art and culture. The advent and development of Buddhism owe a great deal to the ancient land of Pakistan. It was here that the religious activities reached its climax through well-organised missionaries and ultimately made it a world religion.

Above all, it is the land of Gandhara. It is the land where the celebrated faith evolved. More or less a triangle about 100 kilometres across east to west and 70 kilometres from north to south, on the west of the Indus River, the land is surrounded on three sides by mountains. It covers the vast areas of today’s Peshawar valley, the hilly tracts of Swat (Udyana), Buner and the Taxila valley.

Buddhism left a monumental and rich legacy of art and architecture in Pakistan. Despite the vagaries of centuries, the Gandhara region preserved a lot of the heritage in craft and art. Much of this legacy is visible even today in Pakistan.

Pakistan emerged on the world map as an independent sovereign state in August 1947 as a result of the division of the British Empire. With a land area of 881,888 sqkm, its population stands at nearly 210 million. Historically, this is one of the most ancient lands known to man. Its cities flourished before Babylon was built. Its people practised the art of good living and citizenship before the celebrated ancient Greeks.